We combined three approaches: (1) spatial allocation of RFMO-reported catch of highly migratory species (HMS) done by the Sea Around Us (Cashion et al., 2018), (2) catch reconstruction, and (3) analysis of Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) vessel broadcast data. Where available, we used information on catch composition to allocate catch into species or taxonomic groups. Following Pitcher et al. (2002), we created a detailed fishery timeline through extensive searches of the literature, expert interviews, and conversations with Somalis (available at http://securefisheries.org/sites/default/files/SomaliFisheriesTimeline.xlsx). We began our estimation in 1981, when foreign fishing began to proliferate.

Spatial Allocation of Highly Migratory Species Catch

Catch of highly migratory species (HMS) was estimated using the spatialized industrial large pelagic catch data of the Sea Around Us at the University of British Columbia (Le Manach et al., 2016). This dataset harmonizes data from those Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) that manage large pelagic species fisheries including tuna, billfishes, and sharks and reconstructed discard estimates of these fisheries. Members of RFMOs report annually on the amount of fishing catch and effort by gear and location. For Somali waters, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) is the relevant RFMO and it manages 16 species of tuna and billfishes plus commonly caught shark species (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC], 2010). Le Manach et al. (2016) provide a detailed and technical discussion of this methodology.

We selected catch allocations provided by the Sea Around Us (seaaroundus.org, downloaded March 18, 2018) for fish catch in the Somali EEZ for commercial groups Tuna/Billfishes and Sharks/Rays for the following IOTC-reporting countries: China, France, Japan, South Korea, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. Spain and Portugal are part of the EU party. Russia is no longer a party to the IOTC, but they were during the 1990s when they were fishing around Somalia. These countries have a history of reporting spatially explicit data to the IOTC and our creation of the fishery timeline documented a historical presence in Somali waters.

Catch Reconstruction

We modified an established approach to catch reconstruction from Zeller et al. (2007) and Pauly et al. (2014) as follows: first, verify a nation’s fishing presence in Somali waters using searches of the literature and expert input; second, estimate the number of fishing vessels from a particular nation; third, estimate total catch by amount and species composition (where available) for that nation (referred to as anchor points); fourth, extrapolate catch between anchor point years; finally, generate 95% confidence intervals for catch reconstruction time lines using a Monte Carlo simulation and sampling ranges of vessel numbers and catch amounts (Glaser et al., 2015). Confidence intervals from the Monte Carlo simulation were used to provide estimates of uncertainty across all estimates.

This reconstruction approach was used to estimate catch for Italy, Yemen, Iran, Egypt, Kenya, Greece, and Thailand. Details of reconstructions on a country-by-country basis follow.

Italy

Italian vessels fished for tuna during the 1930s through 1950s, but data on volume and catch composition were not available. Three trawlers fishing for Amoroso e Figli operated during 1978–1979, but catch estimates were not available. We collected reliable information on trawlers operating through the joint ventures SOMITFISH (1981–1983) and SHIFCO (1987–2006) (Shifco, 1998). Our reconstruction posits the following: from 1981–1983 three trawlers were operating for SOMITFISH, and from 1987–1989 three trawlers were operating for SHIFCO. In 1987, SHIFCO added two trawlers to its fleet. These vessels were similar in capacity, ranging from 57–66 m in length. Vessels were flagged to Somalia until 1998, and that catch should be attributed to the Somali domestic fleet. Joint venture rules require catch from joint venture vessels be attributed to the flag country. Therefore, catch from these vessels during 1981–1998 should be included in volumes reported by Somalia to the FAO and in the domestic reconstruction of Cashion et al. (2018). When SHIFCO vessels were reflagged, catch should be considered foreign. We assign the flag to Italy because of the history of the joint venture and the exclusive purchasing rights of an Italian import company, Panapesca SpA.

Records of catch and composition by the five SHIFCO trawlers were obtained from Panapesca SpA. Catch was reported in kilograms for various fishery taxa aggregated across all vessels but specific to a fishing campaign (approximately 55 days in length). Records covered August 2000 to September 2006. Annual catch (metric tons) was calculated from these records, and the average catch over the period of observation (3,440 mt) was extrapolated back from 1999 to 1990. Prior to 1990, catch was reduced to 60% of the average observed catch (2,064 mt) because only three trawlers were operating during that period. One trawler, the Antoinette Madre, operated in at least 1984 (Bihi, 1984). Two trawlers landed fish and lobster in 1985, and values (1,313 and 679 mt) were reported by Somali Democratic Republic Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources [MFMR] (1985). We used the average catch by these two trawlers to estimate catch for the Antoinette Madre in 1984 (996 mt). Finally, records (Somali Democratic Republic Ministry of Fisheries, and Marine Transport [MFMT], 1988) show five additional Italian trawlers operated in 1988 and we applied the average annual catch from the five SHIFCO vessels (3,440 mt) to this datum. This value is bolstered by a report (Van Zalinge, 1988) that one SHIFCO trawler landed 1,245 mt in 1987. Catch composition also was obtained from Panapesca record sheets. For most reporting periods, finfishes were aggregated across species. However, for records from August 2000 and September 2006, we obtained family level data. We applied this composition breakdown to the larger “fish” categories from remaining reporting periods. All five former SHIFCO vessels stopped operating in Somali waters in 2006 due to high fuel costs.

Yemen

One of the earliest mentions of fishing by Yemen occurs in Yassin (1981), in which he refers to a concern about shared resource management for the Indian oil sardine. There is no mention of Yemeni boats crossing over into Somali waters; it is implied that the resource spans both territories. Therefore, we take 1981 as an anchor point for which Yemeni catch in Somali waters was zero. Twelve Yemeni vessels were arrested in Somali waters in 2006 (our minimum number of vessels), and the UN claims as many as 300 Yemeni vessels fish in Somali waters each year (United Nations Security Council, 2013). The State Minister for Fisheries and Marine Resources in Puntland reported that Yemeni vessels carry between 3–7 mt of fish per trip, make three trips per month, and visit Somali waters each month out of the year (Kulmiye, 2010). Therefore, our Monte Carlo simulations of catch by Yemeni vessels calculated annual catch by sampling over a triangle distribution limited by minimums of 12 vessels per year and 108 mt per vessel, and maximums of 300 vessels per year and 252 mt per vessel. This estimate was applied to 2006–2014, and catch was linearly interpolated back to 1981 (where the anchor point was zero).

Yemen reported catch to the IOTC during the period of 2003–2007, and we used the reported IOTC data to guide our species composition estimates: yellowfin (48%); other tunas such as longtail, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, frigate tuna, and kawakawa (combined with undifferentiated tuna, 38%); and sharks (5%). All data reported to the IOTC originate from boats deploying handlines.

Iran

Our approach to estimating catch from Iran was identical to that used to estimate catch by Yemen. Reports in the literature indicate Iran has a minimum of 5 (Anon, 2013) and a maximum of 180 gillnet vessels operating in Somali waters (United Nations Security Council, 2013). Capacity for fish on each vessel was not available. We therefore used global estimates for gillnet vessels to obtain a range of catch per year. Pauly et al. (2014) estimated catch capacity for gillnet vessels as 221 mt per year (average) and 1,211 mt per year (maximum). Waugh et al. (2011) estimated the minimum capacity of these vessels to be 16 mt per year. Our simulation therefore resampled triangle distributions estimating number of vessels and fish capacity.

Egypt

Trawling by Egyptian vessels began in 1981. Haakonsen (1983) reported “a few” and no more than 10 trawlers operating in the early 1980s, split between Italy and Egypt. Knowing Italy had three trawlers operating in 1981, we assigned a conservative three trawlers as an anchor point in 1981. Further, we assigned anchor points of 36 trawlers during 2003–2006 (Berbera Maritime and Fisheries Academy, 2013) and 34 trawlers in 2007 (Anon, 2012). Published estimates of catch by these trawlers are 30 mt per trawler per month; of that, 5% of catch was shrimp and the remainder was finfish. We extrapolated back to zero catch in 1981. Variable estimates of numbers of boats or capacity were not available, so we did not conduct Monte Carlo simulations to estimate confidence intervals.

Kenya

Since 2004, Kenyan trawlers fished for prawns along the Juba River on the border with Somalia (Bocha, 2012). Waldo (2009) reports 19 illegal trawlers caught 800 mt of prawns each year since that time. We did not conduct Monte Carlo simulations for Kenyan catch.

Greece

Greek vessels have been trawling in Somali waters since the 1960s. “A few” trawlers were operating in the mid-1960s (Haakonsen, 1983) and “a number of” additional trawlers were fishing in 1983 (Bihi, 1984). From 1983–2010 we uncovered no evidence of trawling from Greece. In 2010, two Greek trawlers flagged to Belize, the Greko 1 and Greko 2, appeared. We therefore estimated two trawlers fishing in 1983 and two from 2010–2014. These vessels operated in Southern Somalia and may have been properly licensed. We found no information on catch rate but each vessel was 193 gross tonnage (GT, MarineTraffic.com, 2015), so we assumed the vessels were similar in catch composition and catch rate to the Korean-flagged trawlers described below. Therefore, we used the same fish catch per GT from the Korean trawlers (1.16 mt per GT) to the Greek trawlers, equaling 447 mt per year.

Thailand

From 2005 to 2009, seven Thai trawlers, owned by Sirichai, were licensed to fish year-round in Puntland. The trawlers operated continuously 6 months by transshipping to a Thai freezer ship in Somali waters, and they went to the port in Salalah (Oman) for repairs and unloading twice a year (Fry, 2009). We did not find reports of catch for these vessels. Given the similarity in location and gear, we used the reconstruction of catch for Korean trawlers (see below) for these vessels, equaling 785 mt of fish catch per year. Thai vessels reportedly stopped operating in Somali waters by 2009, although in 2018 their presence has again been observed.

Automatic Identification System Analysis of South Korean Trawl Fleet

Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) are used for collision avoidance and tracking of vessels at sea. Vessels greater than 300 GT, including fishing vessels, are required by the International Maritime Organization to broadcast AIS. Many fishing vessels smaller than 300 GT may broad AIS voluntarily for safety reasons.

Preliminary observation of AIS pings (purchased from a subscription to ShipView) and expert input identified seven vessels flagged to South Korea that were likely bottom trawling in Somali waters. These vessels ranged in size from 49–68 m long and 439–888 GT. Using the Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) numbers associated with these seven vessels, we purchased satellite AIS data for all seven boats from exactEarth (Cambridge, Ontario, Canada, March 26, 2015). These data include every broadcast point from the ships in question during July 2010 through December 2014. Each point includes a position (latitude/longitude) as well as associated vessel information such as IMO number, vessel name, flag, size, date, time, speed over ground (SOG), and course over ground. Vessel operators can control when and what they broadcast. Often points had missing information (e.g., SOG was not included in a broadcast) or AIS may have been turned off altogether, creating gaps in the dataset. As a result, estimates made from these data are conservative.

Using ArcGIS 10.3, we identified transmissions within the boundaries of the Somali EEZ. Then, using SOG communicated during those transmissions, we classified where the vessels were actively trawling by creating a histogram of SOG (Figure 2), and choosing the range of speeds defining the peak in SOG. This method of using SOG distributions to identify trawling activity has been shown to correctly identify 99% of real trawling activity (Mills et al., 2006). Trawlers 2 and 6 were present in Somali waters and were likely trawling but did not broadcast SOG.

FIGURE 2

Figure 2. Histogram of speed over ground (knots) reported by Automatic Identification System pings from seven South Korean-flagged trawlers during 2010–2014. Active trawling was classified from SOG distribution.

Next, we used the times and dates of transmissions during active trawling to calculate the number of days trawled during the time period for which we had AIS data. If there were multiple transmissions at trawling speed in 1 day, we classified that as a trawling day. Each vessel was in Somali waters for differing durations, so we counted trawling days per boat and then calculated the ratio of active trawling days to the number of days in a year for which AIS transmissions were available. This ratio was then multiplied by 365, generating an estimate of days trawled per year for each vessel. Using the same procedure, we calculated the mean proportion of days trawled per month across all boats. To estimate active trawling days per month for the two vessels that did not broadcast SOG, we determined the number of days per month those two vessels were in the Somali EEZ, then multiplied by the mean proportion of days trawled calculated from the other boats during the associated month.

Because the dataset for each boat did not always include an entire year of data at the beginning and end, we used a similar proportional method to estimate days trawling per year for all seven boats. For a single boat, we took the proportion of days trawled to the number of days over which we had data in a given year, then multiplied by the number of days in that year.

We obtained ocean depth at the location of AIS transmission by overlaying transmission points with a bathymetry raster (GEBCO Compilation Group, 2019). To calculate the total area trawled, we used the mean SOG from all boats during active trawling and multiplied by a likely width of the trawl for vessels of comparable size (49 m; Gomez and Jiminez, 1994) and by the average number of hours spent trawling per day. For robustness, we also calculated straight-line distance trawled per boat per day. For each AIS transmission point, we drew a straight line to the next consecutive point, then calculated the combined distance of all the line segments for a single day. We multiplied this distance by the assumed width of the trawl to get a second estimate of total trawled area.

Weight and species composition of catch were obtained from catch certificates submitted to the European Union for two of the vessels. The dated certificates spanned 7 months and contained catch by species of fish and invertebrates for each month. From the AIS data, we know how many days per month those two trawlers were operating in Somali waters. To estimate catch per day for a trawler, we divided catch per month by the number of days trawled in the same month.

Sustainability Analysis

The sustainability of fish stocks in Somali waters has never been assessed, and most stocks lack the data necessary for national-level stock assessment. We classified the sustainability of Somalia’s fish stocks at current levels of foreign and domestic catch using methods developed for data-poor fisheries (Costello et al., 2012). We chose species groups that are commercially valuable and had sufficient data for analysis, excluding tuna and billfishes. These latter groups are analyzed by the IOTC and we report their sustainability classifications. We used our estimates of catch for dolphinfish, emperors, goatfish, jacks, clupeids (sardines), snappers, sharks, rays, groupers, and grunts.

Sustainability was classified based on models used to predict the ratio of biomass (B) to biomass needed for maximum sustainable yield (BMSY). We used the panel regression model developed by Costello et al. (2012) to estimate B/BMSY for these ten fish groups. Where catch time series were reported for species, they were aggregated up to the family (or near-family) level. We combined catch reconstructions of Somali domestic fisheries (Persson et al., 2015; Cashion et al., 2018) with our estimates of foreign fishing to create estimates of total catch for these species groups.

B/BMSY is a measure of the current standing stock (B) of a fish stock compared to the biomass needed to support MSY. For B/BMSY < 1.0, biomass is below that needed for MSY, and fishing should be reduced to improve sustainability. For B/BMSY > 1.0, biomass is above that needed for MSY, and fishing levels should stay the same or potentially increase. B/BMSY is a function of a suite of fishery characteristics, including (but not limited to) life history characteristics such as size, growth patterns, or age at reproductive maturity, and catch characteristics such as how quickly a fishery developed, how long it has existed, or whether catch has peaked. Costello et al. created a regression model that relates B/BMSY to these characteristics. They analyzed 204 assessed (data-rich) stocks from around the world. The B/BMSY calculated for these stocks was validated by independent stock assessments. Six nested regression models, each containing a different set of explanatory variables to accommodate varying data availability, were generated. Next, the coefficients estimated for these 204 stocks were then applied to 1,793 unassessed (data-poor) stocks to estimate B/BMSY. We used their published coefficients on each catch time series mentioned above.

Specifically, for fishery i, fish family type j, and calendar year t, a multivariate panel regression model estimated B/BMSY as:

log(B/BMSY)ijt=α+βXijt+γi+δt+εijtlog(B/BMSY)ijt=α+βXijt+γi+δt+εijt

where α is a constant term, β relates the fishery characteristic Xijt to B/BMSY, γi is a family fixed effect, δ is a time trend effect, and eijt is an error term. For the fish groups we included, data for fish maximum length were available but von Bertalanffy K, geographic distribution, and temperature preference were not uniformly available. We therefore chose Model 5 published in Costello et al.’s supplementary materials.

Most parameters were calculated directly from the time series of catch. Maximum length data were obtained from FishBase (Froese and Pauly, 2014). We created a database of over 800 species known to occur in Somali waters (available at http://securefisheries.org/report/securing-somali-fisheries) and these species guided our choice of length values to select from FishBase. To calculate a length value to include in the regression model, for a given family/species group, we averaged maximum length values for the species that occur in Somali waters. Although the Cashion et al. (2018) domestic reconstruction extends back to 1950, we truncated the time series to cover only 1981–2014 to overlap with our foreign reconstruction. Catch data were most robust from 1981–1987 due to relatively more reliable data collection and reporting by the Ministry of Fisheries under the Siad Barre regime (Fry, 2009). Following Costello et al., we further truncated catch time series to begin once catch reached 15% of the maximum value in the record. This reduces noise associated with behavior attributed to fishery “ramp-up” in the early years of a fishery. For most series, the value in 1981 was greater than 15% of maximum catch, so no further truncation was applied. All analyzed catch time series had at least 7 years of continuous data, the minimum required by Costello et al. to make the approach valid.

We report sustainability classifications for IOTC-assessed species (yellowfin tuna, bigeye tuna, skipjack tuna, swordfish, longtail tuna, blue marlin, and striped marlin) based on their formal stock assessments. Given these highly migratory species are in Somali waters only part of the year, our estimates of annual catch for them in Somali waters are not appropriate for the panel regression approach to classification. Additionally, IOTC brings expert analysis and knowledge to bear on these species. Their approach calculates B/BMSY as well as F/FMSY (where F is fishing mortality). They classify sustainability according to a red-orange-yellow-green 4-cell contingency (e.g., Indian Ocean Tuna commission [IOTC], 2014) that incorporates B/BMSY and F/FMSY. To make their analysis comparable to ours, we translated those species classified as orange to green, and those classified as yellow to red. For current stock assessments and classifications, see http://www.iotc.org/science/status-summary-species-tuna-and-tuna-species-under-iotc-mandate-well-other-species-impacted-iotc.

Results

Foreign Fishing in Somali Waters

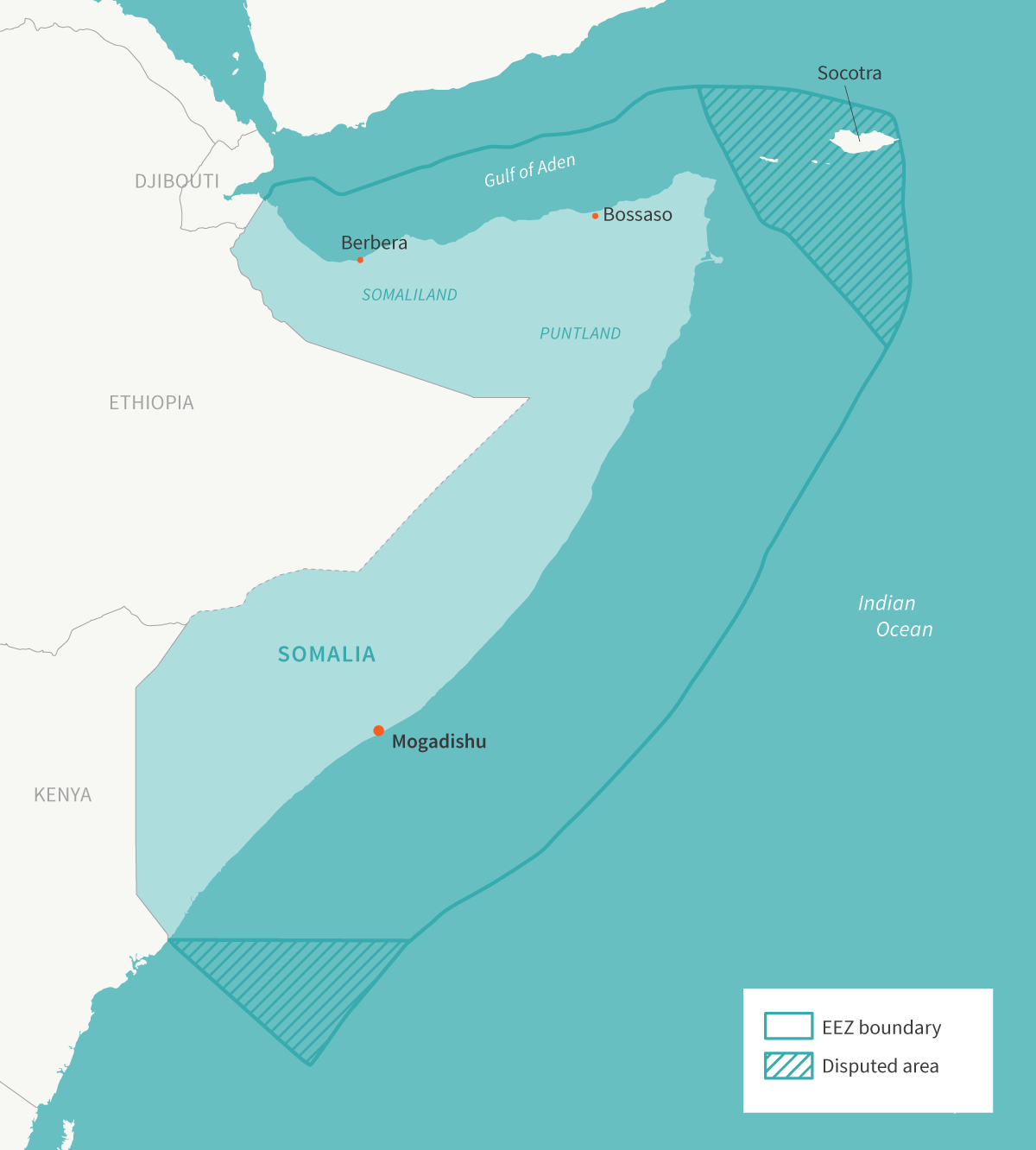

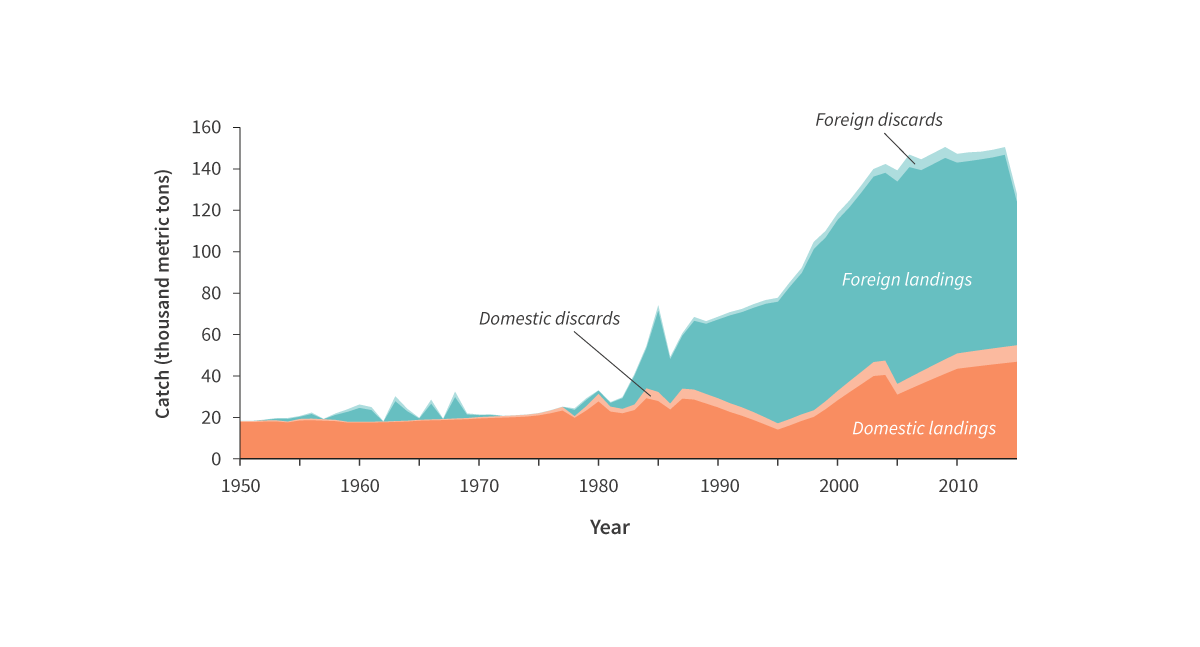

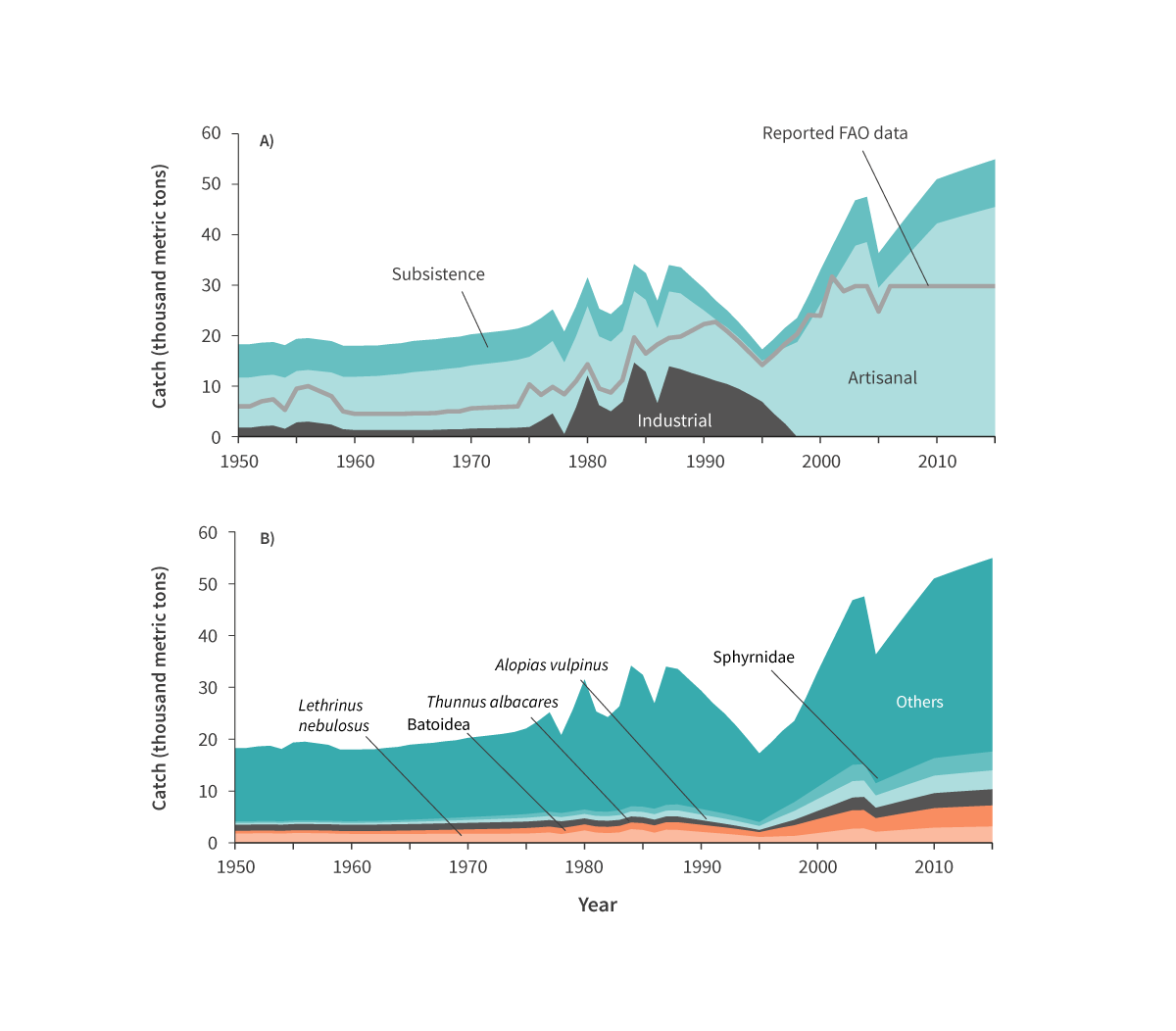

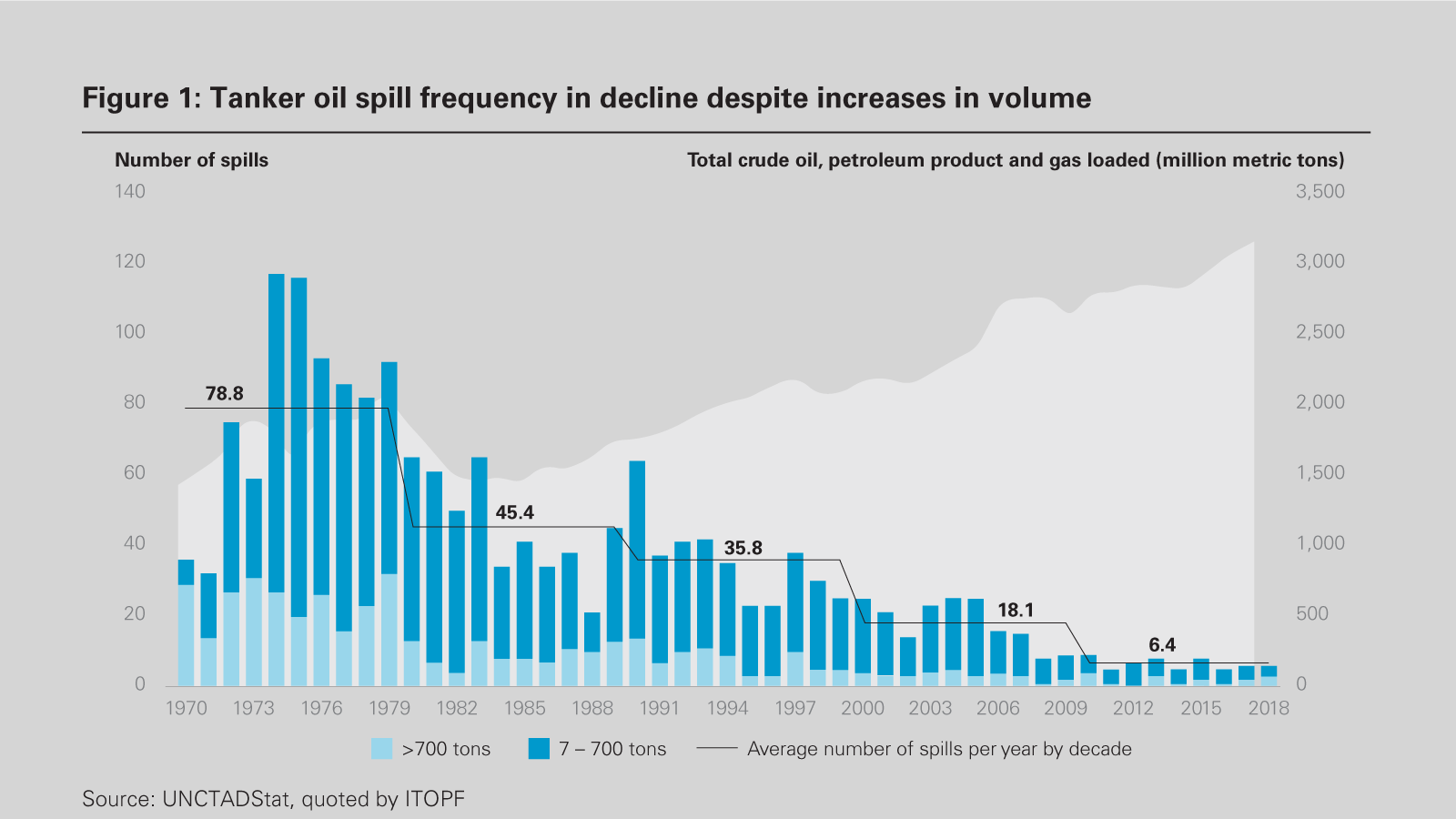

We estimate foreign fishing vessels operating in the EEZ of Somalia landed approximately 2,521,318 mt of fish between 1981 and 2014 (Table 1 and Figure 1). During that same period, Somali domestic fishing vessels caught only 1,182,995 mt (Cashion et al., 2018). In 2014, foreign vessels caught 92,537 mt, nearly twice as much as the Somali domestic catch of 54,177 mt. The peak of foreign fishing occurred in 2003 (132,458 mt) as smaller regional fleets became firmly established, but before distant water fleets withdrew from Somali waters to reduce the risk of piracy (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC], 2008). In 2014, Iran and Yemen accounted for 79% of all fish caught by foreign vessels in Somali waters. There is considerable uncertainty in these estimates. Our Monte Carlo simulations of Yemen and Iran provide confidence intervals, which are quite wide. For estimates based on reported catch, there are not estimates of uncertainty but the point estimates should be considered a minimum.

TABLE 1

Table 1. Catch (mt) of by foreign-flagged fishing vessels in Somalia’s exclusive economic zone.

FIGURE 1

Figure 1. Estimated (reconstructed) catch by foreign and domestic fishing vessels in Somalia’s exclusive economic zone, 1981–2014. Domestic catch reconstruction by Cashion et al. (2018).

Spatial Allocation of HMS Catch

Fishing by distant water fishing nations in Somali waters has declined significantly in recent years. These fleets of purse seine and longline vessels target tuna and other large pelagics as they migrate through the Western Indian Ocean. In 2003, we estimate these fleets caught about 44,000 mt of HMS in Somali waters. The decline in catch around 2005 was driven by several factors: the movement of all purse seine vessels out of Somali waters (Chassot et al., 2010), the southward movement of the purse seine and longline fleets (Indian Ocean Tuna commission [IOTC], 2014), and a peak in pirate activity (Oceans Beyond Piracy, 2015) that caused vessels to avoid Somali waters. In 2014, we estimate distant water fishing nations caught only 532 mt of HMS in Somali waters.

Catch Reconstruction

Italy

Fishing by Italian vessels in Somali waters follows their colonization of the Horn of Africa. As early as the 1930s, Italy operated two tuna canneries in northern Somalia (Bihi, 1984). Italian vessels fished for tuna through the 1950s and trawling for coastal demersal fishes (mostly reef-associated) and cephalopods lasted from the late 1970s until 2006. We estimate Italian trawlers landed 74,000 mt of fish between 1981–2006. After Italian trawlers departed in 2006, South Korean trawlers took over the same fishing grounds and export market.

Yemen

We find fishing boats from Yemen began appearing in the waters around Somalia, especially near Somaliland, in the early 1980s (Yassin, 1981). At the time, arrangements between Yemeni and Somali fishers was mutually agreeable and access agreements were available. In Puntland, Yemeni fishers purchased fish from Somali fishers and, until recently, this was a major trade. Yassin (1981) anticipated future conflict over the migrating Indian oil sardine if cross-border fishing continued. We estimate that, in the most recent years of analysis, Yemen caught 28,970 mt of fish in Somali waters each year (CI90% = 11,094–50,076 mt). The civil war in Yemen, which began in 2015, has significantly reduced the number of Yemeni vessels coming to fish in Somali waters (Glaser, 2015).

Iran

Iran’s recorded fishing fleet had about 6,363 boats in 2007, 1,296 of which are authorized by the IOTC to fish outside Iranian waters (Waugh et al., 2011). In recent years, we estimate Iranian vessels catch about 44,850 mt of tuna and sharks each year (CI90% = 8,988–104,150 mt). IOTC reports show most of this catch to be yellowfin and skipjack tuna, and the gillnet vessels have significant amounts of bycatch including billfishes, sharks, rays, and mammals (Waugh et al., 2011). Somali officials have recently focused their attention on fishing by Iranian vessels, and they formally accused Iran of fishing illegally by submitting evidence to the IOTC in 2015 (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC], 2015).

Egypt

In the early 1980s, Egyptian trawlers took over the fishing niche previously filled by the Soviet joint venture SOMALFISH (Yassin, 1981). We estimate 34 trawlers caught 12,240 mt per year (2007–2014) and 36 trawlers caught 12,960 mt per year (2003–2006). These trawlers appear to have obtained licenses from the government of Somaliland through the mid-2000s. However, public opinion and law enforcement has shifted against these trawlers recently. Licenses to Egypt were ended by Somaliland in 2012 (Government of Somaliland Ministry of Trade and Investment, 2014). In 2009, two trawlers were arrested By Somaliland forces in Las Koreh (Anon, 2010b) and another was arrested in 2014 (BBC, 2014).

Kenya

Since 2004, Kenya has operated trawlers that target prawns near the mouth of the Juba River along the border with Somalia (Bocha, 2012). Waldo (2009) reported nineteen illegal trawlers caught a total of 800 mt annually. The Kenyan prawn fishery has been accused of contributing to the bycatch of endangered sea turtles that nest along the Somalia-Kenya border (Megalommatis, 2008). Recently, fishing in these waters has been banned by the Kenyan government in response to concerns about the presence of Al-Shabaab.

Greece

Trawlers from Greece started fishing in Somali waters in the 1960s but we found no reports of their presence between 1983 and 2010. In 2010, two trawlers, the Greko 1 and Greko 2, began operating and we estimate they catch 447 mt of fish per year. These two vessels have become controversial. In 2016, Somalia asked for help from regional ports to prevent the Greko 1 from landing its catch. At that point, Somali officials denied Greko 1 was legally licensed and the vessel has been under investigation by FISH-i Africa, a regional information sharing task force (Stop Illegal Fishing, 2017).

Thailand

Thai fishing vessels have been documented in Puntland from at least 2005 to 2009. The Puntland Coast Guard supplied three officers to protect a Thai trawler owned by the Thai seafood company Sirichai around 2006 (Puntland State of Somalia Office of Coast Guard Forces, 2006). The company owned and operated seven licensed trawlers in Puntland’s waters. The growing threat of piracy caused Thai vessels to leave Somali waters. In November 2008, the trawler Ekawatnava 5 was sunk by the Indian navy when it mistook the vessel for a pirate mothership. Fourteen Thai crew members were killed (United Nations Security Council, 2013). The Thai Union 3 was hijacked in October 2009 and its crew held until March 2010. We estimate these trawlers caught 5,495 mt each year from 2005–2009.

AIS Analysis of South Korean Trawl Fleet

Catch records and AIS transmissions suggest seven South Korean-flagged trawl vessels caught 27,475 mt during 2010–2014, or approximately 5,495 mt of catch attributable to this fleet. Based on import records, catch consisted largely of cephalopods (cuttlefish = 20%, squid = 19%). Most fish catch was emperors (Lethrinidae; 17%), followed by barracudas (Sphyraenidae; 9%), and grunts (Haemulidae; 7%). Each of these vessels was present and actively trawling in Somali waters for an average of 229 days per year (Table 2). During May through January, these vessels trawled 73 to 87% of days in any given month. Trawling was reduced during the period of heavy seas in February through April, occurring during 34 to 62% of days in these months.

TABLE 2

Table 2. Days per year spent actively trawling within Somalia’s exclusive economic zone boundaries for seven South Korean-flagged vessels.

Figure 3 shows the location of trawling; the vast majority occurred in inshore waters of Puntland because the government of Puntland has regularly issued trawling licenses to foreign fleets. Additionally, the continental shelf topology facilitates high fish abundance. Ninety-five percent of all trawling we tracked occurred inside the 75 m depth contour (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Figure 3. Density of AIS pings during active bottom trawling from seven South Korean-flagged trawlers during 2010–2014.

The mean SOG from all boats during trawling was 3.9 knots. Multiplying by the assumed width of the trawl for vessels of comparable size (49 m, Gomez and Jiminez, 1994) and by the average number of hours trawling per day (8.4 h) and converted into km2, we estimate each vessel trawled 3 km2 per day of active trawling. Multiplied by the number of days trawled per year by each boat, we estimate this fleet trawled 120,652 km2 during 2010 – 2014. Our robustness check generates a similar estimate. Total straight-line distance trawled was 2318 km. Multiplied by the assumed width of the trawl (49 m), a second estimate of the trawled area is 113,593 km2.

Sustainability Analysis

We classify as unsustainable 10 of 17 fish groups included in our analysis (Figure 4), including swordfish, striped marlin, yellowfin tuna, longtail tuna, emperors (including the commercially important spangled emperor, Lethrinus nebulosus), goatfish (Mullidae), snappers (Lutjanidae), sharks, groupers (Serranidae), and grunts (including the commercially important painted sweetlips, Diagramma pictum).

FIGURE 4

Figure 4. Sustainability classification of commercially important fish groups caught in Somali waters.

This data-poor approach has limitations that should be considered. We analyzed groups of fishes that ranged from taxonomic organization at the species level (e.g., skipjack tuna) to superorder (e.g., sharks; see Figure 5). For those groups whose catch series came from catch reconstruction, there is higher levels of autocorrelation. However, Costello et al. (2012) found results were robust to assumptions of catch underreporting and misreporting. Our approach imposes a brightline (B/BMSY = 1.0) for the classification of sustainability (above 1.0 = sustainable), but small changes in reconstruction series could cause a group to cross that line. Finally, our classification approach does not distinguish those groups which are need immediate conservation measures.

FIGURE 5

Figure 5. Sustainability analysis for sharks based on estimated B/BMSY using catch reconstructions for foreign and domestic fleets in Somali waters. When estimated catch (dashed line) exceeds B/BMSY (solid line), the fishery is classified as unsustainable.

Discussion

Since 1981, foreign fishing in Somali waters has been characterized by: purse seine and longline distant water fleets from Europe and Asia that target HMS, fish offshore, and tend to report to management authority of the IOTC; nearshore trawling for coastal species by various nations including South Korea, Greece, Italy, and Kenya; and gillnet or artisanal fishing by regional fishing nations such as Yemen and Iran that appear to fish for a wide variety of species, including sardine, tuna, and sharks.

Both the reality and perception of foreign fishing has perpetuated instability in Somalia. Somalis have accused foreign vessels of shooting at them (Katz, 2012), spraying them with boiling water, and purposely destroying their fishing gear. Some fishers claim they fear for their lives from aggressive foreign vessels (Lehr and Lehmann, 2007). Growing public anger has caused a backlash against foreign fishing. For example, Egyptian trawlers that had once received legal fishing licenses have recently been arrested (BBC, 2014). We propose five mechanisms by which foreign IUU fishing drives instability in Somalia: (1) foreign competition with domestic fleets for fish, (2) links between foreign fishing and piracy, (3) effects of nearshore trawling, (4) conflict between state and federal governments over modalities for licensing foreign vessels, and (5) a long-term reduction in livelihood security.

Competition Between Foreign and Domestic Fishers

The presence of foreign fishing vessels in Somali waters is not inherently problematic, but if there is strong overlap in the target species, we expect higher levels of conflict to evolve. Comparing the catch of commercially important fish groups by foreign (this study) and domestic (Cashion et al., 2018) fleets over the past decade (2005–2014), we find overlap to be significant (Figure 6). Of the 18 species groups caught by foreign vessels, 15 are also caught by domestic fishers. Our sustainability analysis showed that five of the species groups caught by both foreign and domestic fishers are currently being fished at unsustainable levels. These include sharks, emperors, groupers, snappers, and goatfishes, which equal 56% of domestic catch during the most recent decade. Furthermore, tuna stocks are targeted by both fleets, and two of four species commonly caught in Somali waters are classified as unsustainable by IOTC. The similarity in catch composition suggests foreign gillnet vessels are likely competing for access to the same fishing grounds as the domestic fleet, especially for demersal species such as emperors and groupers. Our AIS analysis shows foreign trawlers have been operating well within the 24-nm territorial sea reserved for Somali fishers in the Somali Federal law.

FIGURE 6

Figure 6. Overlap of catch composition for foreign and domestic fleets fishing in Somali waters. Total catch per species group calculated from catch estimates during 2005–2014.

For context, however, it is important to note that fishing has not been a large contributor to income or diet in Somalia. Current estimates are that only 30,000 fishers live in Somalia, but there is a lack of solid, current information on the number of fishers in Somali fishing communities. Additionally, cultural attitudes toward fish eating and ocean conditions that hamper fishing activity in many parts of the year have limited the significance of fishing to the overall Somali economy (Yassin, 1981).

Piracy

In the literature, piracy is frequently linked to IUU fishing (Murphy, 2011; Sumaila and Bawumia, 2014). After the beginning of the civil war in 1991, Somali waters were left without legitimate capacity for enforcement of maritime sovereignty or boundary integrity. Organized groups of fishers began targeting first foreign fishing vessels and later, commercial traffic, partly in response to the perception that the international community ignored or even encouraged illegal fishing (Lehr and Lehmann, 2007). Initially, these attacks were limited to small-scale theft. In 1994, two SHIFCO fishing vessels were hijacked and the crew were held and then released for ransom, leading to an escalation in pirate tactics (Kulmiye, 2001). These small-scale attacks were quickly appropriated by warlords with criminal networks and international financing. These criminals sought to maximize profit above all else by attacking any vessels passing in and beyond Somali waters (Hansen, 2011; Schbley and Rosenau, 2013).

At the same time, warlords sold licenses to foreign vessels in return for protection against pirate attacks (Sumaila and Bawumia, 2014). By 1998, these agreements had ended because, for the most part, warlords did not provide the protection they promised. By the early 2000s, loosely organized pirate gangs had fully evolved to a highly organized business model that brought in substantial currency (Burale, 2005) and targeted any vessel passing in and beyond Somali water, not just fishing vessels (Schbley and Rosenau, 2013). Finally, adding to the complexity, the warlords who justified their actions through protection of Somalis had actually enabled IUU fishing by providing armed security and legal means to obtain licenses (Oceans Beyond Piracy, 2015).

The international community deployed NATO-led naval vessels to patrol waters around Somalia to tackle piracy, but very little has been done to stop illegal fishing. Some Somalis see this as tacitly enabling illegal fishing (African Development Solutions, 2015). Pirate attacks, which in 2014 were reduced to zero successful (reported) attacks, have again targeted fishing vessels. Several Iranian fishing vessels were captured in April 2015, and at least 37 fishers were taken hostage (Oceans Beyond Piracy, 2015). A second Iranian vessel, likely fishing illegally, ran out of fuel and drifted onto shore in El-Dheer, an Al Shabaab stronghold in 2015 (Anon, 2015c). After paying a “fishing fee,” the crew and cargo were released.

Effects of Nearshore Trawling

Foreign trawlers operated in Somali waters from the mid-1970s until 1991 as joint ventures. Specially, agreements between the Somali federal government allowed joint ventures with Italy, Egypt, Greece, Japan, France, the Soviet Union, Singapore, and Iraq (Glaser et al., 2015). Most of these licensed ventures dissolved after 1991 but many of the trawlers continued operating. Thirty-six trawlers from Egypt operated along the northern coast. Five Italian vessels belonging to SHIFCO operated until 2006, at which time South Korean trawlers took over. Two Greek trawlers, the Greko 1 and 2, have operated since 2010. According to the 2014 Somali Fisheries Law (Article 33.1), all bottom trawling is illegal. Today, bottom trawling is illegal under the new Somali Fisheries Law (Article 33.1).

The damage done to the benthic ecosystem is impossible to assess because there is no scientific baseline for comparison (Anon, 1976; Stromme, 1984). In this study, we estimate seven trawlers alone trawled over 120,000 km2 in 5 years. We argue these estimates are conservative and likely underestimates because they were strictly derived from observable AIS tracks that were voluntarily transmitted. While we do not know the specific effects of this trawling on the Somali marine environment, a large body of literature on bottom trawling shows tremendous and long-lasting negative impacts due to high mortality of bycatch (Alverson et al., 1994), disruption to biogeochemical systems linking the water column to the benthos (Pilskaln et al., 1998), and significant reductions in biodiversity and productivity due to high mortality on the benthic community (corals, sponges, echinoderms, and mollusks (Dayton et al., 1995; Kaiser et al., 2006).

Four decades of unregulated and unreported bottom trawling means there is a high likelihood that considerable ecosystem damage has already occurred (Glaser et al., 2015). A global meta-analysis showed trawling of the type occurring in Somali waters (otter trawling) removes 6% of organisms with each pass over an area (Hiddink et al., 2017), and Kaiser et al. (2006) showed that a 20% recovery of trawl-impacted ecosystems could take more than 8 years. For the most heavily trawled locations (Figure 3), benthic communities might never recover before being disturbed again (Collie et al., 2000).

Unclear governance structures have resulted in conflicting guidelines for ports in which trawl vessels attempt to land their catch. In 2015, two trawlers left Mogadishu with a cargo of fish (Anon, 2015a). These vessels were then inspected in Mombasa, Kenya. Somali authorities prevented at least one of these trawlers from landing in Salalah, Oman (EJF, 2015) by invoking the Port State Measures Agreement, an international agreement to which Oman is a signatory and which clamps down on IUU fishing. Eventually, though, one trawler landed its cargo in Yemen, while the other successfully unloaded in Oman after presenting a license from Puntland (Stop Illegal Fishing, 2016). The South Korean-owned vessels continued to fish in Somali waters intermittently through 2017. Four of the vessels reflagged to Somalia in 2015. A fifth vessel’s activity ended in dramatic fashion in 2015 when it sank off the coast of Puntland. The crew was rescued by the Puntland Maritime Police Force.

In early 2017, seven Thai-owned, Djibouti-flagged trawlers were operating off the coast of Puntland. Though their operation is in direct violation of the federal Somali fishing law, they successfully petitioned the Puntland Government for fishing licenses and operated for 6 weeks, when they were joined by a reefer vessel which presumably picked up their illegal catch. These vessels’ blatant disregard for federal law, in addition to the suspicion of human rights violations on board including slavery and human trafficking, led many of the vessels to be detained in various locations and charges have been filed against individuals associated with the vessels and the direct or beneficial ownership companies (Stop Illegal Fishing, 2018).

Recently, bottom trawling has come under scrutiny by international bodies and by local fishing communities (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC], 2015). Trawling in shallow water–and hence close to shore–draws attention to their activities when visible to coastal communities. Some trawlers have reflagged to Somalia in an effort to circumvent the law (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC], 2015). However, bottom trawling is illegal for domestic as well as foreign vessels. Trawlers have come to symbolize the conflict between domestic and foreign fishing fleets in Somalia (Kulmiye, 2010; Coastal Development Organization, 2013; Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC], 2015). The competition for space in these productive fishing areas has led to antagonistic behavior by foreign vessels toward Somalis. Incidents like these could increase as resources decline, intensifying competition for dwindling resources.

Conflict Over Licensing Foreign Vessels

Somali authorities have worked to draw international attention to illegal foreign fishing. In April 2015, the Somali delegation presented evidence of illegal fishing at the annual IOTC conference, including vessel tracks, photographs, and documentation of expired licenses (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC], 2015). AIS showed nine Chinese longline vessels fishing illegally for HMS during March and April 2015 (Glaser et al., 2015). Although the Chinese delegation recalled their vessels immediately, at least some of these vessels returned 2 months later with licenses issued by the Federal Government of Somalia.

Recognizing the need for clear and comprehensive laws and regulations, fisheries ministers, policy makers, and international actors are working to improve and expand legislation around Somali fisheries. Inshore fisheries development is left to the discretion of federal member states (e.g., Puntland) and offshore fisheries are managed by the federal government in coordination with member states.

Governance mechanisms that promote sustainable management with effective monitoring and enforcement of the Somali fisheries sector are needed to support long-term food, economic, and maritime security along Somalia’s 3,000 km coastline. However, governance of the Somali fisheries sector is wrought with challenges.

One such challenge is the lack of continuity between federal and member state laws and policies. Somalia’s federal fisheries law is not mirrored in the regional member state laws, creating jurisdictional conflicts. This ambiguity has enabled states to disregard federal law in the past; for example, some states previously issued licenses to foreign vessels or permitted bottom trawling (which is clearly banned in the federal law). The federal government, in 2018, requested all prior-issued licenses be canceled, and federal member states complied. There are on-going efforts to rewrite the federal fishing law (adopted in 2014) and to update the constitution to make all state laws subordinate to the federal, but this is a lengthy process and requires Parliamentary approval.

At one point, disagreement between member states and the federal government stalled progress toward effective fisheries governance. Since declaring the Somali EEZ in June 2014, policy makers have not created a federal fisheries authority to manage fishing. Meetings between fisheries ministers of the member states and the federal government between 2014 and 2017 helped build consensus on the role and responsibilities for management at each level of government. Agreements reached in April 2014, May 2016, and May 2017 specified that the federal government would have licensing jurisdiction over HMS in non-territorial waters. In 2018, a licensing agreement was finally adopted, but one issue to still resolve is how to divide revenues from that licensing.

There are ongoing discussions over how to divide licensing fees between the state and federal governments. While fisheries experts support earmarking license revenue for building a federal fishing authority and investing in the Somali fishing sector, license revenue could also be used to support the security sector and economic development. These competing needs have stalled agreement on licensing modalities, which in turn delayed both the inflow of revenues and implementation of offshore fisheries management.

Our research shows six nations were fishing in Somali waters in 2014, but before the peak of piracy, over 13 nations were actively fishing for HMS inside Somali boundaries. Today, many foreign fleets (particularly those from the EU) have expressed interest in acquiring fishing licenses if the Somali government develops a legitimate and reliable licensing scheme. In early 2019, the Federal Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources issued licenses to 31 Chinese longline vessels to fish for HMS in the Somali EEZ outside the 24 nm buffer reserved for Somali domestic fishers, earning $1 million in revenue for the government. The agreement resulted from successful negotiations between the federal government and member states, and it sets the stage for future negotiations on resource management. But the licensing of these vessels has been controversial within Somalia and public backlash has occurred over fears that foreign fishing vessels will outcompete or harm domestic fishers.

Long-Term Reduction in Livelihood Security

In coastal communities, nearshore fisheries offer opportunities to build resiliency through food and economic security. Reliable access to food and stable food prices are a key component of such resiliency (McClanahan et al., 2015), which can reduce the likelihood that tensions turn into violence (Hendrix and Brinkman, 2013). If sustainably developed and managed for the long-term, fisheries can support stable and durable communities. Given a lack of long-term monitoring of Somali marine resources, there is considerable risk overexploitation will be undocumented until a tipping point has passed. At that point, artisanal fishers will be facing severe livelihood insecurity. Federal and state ministries lack the resources to build out management capacity in their own ministries, let alone in local communities. Lack of resources and funding is inadvertently creating a cycle of support for expanding foreign fishing operations in Somali waters while support for local communities lags far behind.

Conclusion

Since 1991, Somalis have not had a viable way to manage the risks to their domestic fisheries. Illegal foreign fishing provided a form of moral justification for the rise of piracy to protect valuable marine resources. But piracy is not an inevitable reaction to foreign fishing. Conflict with foreign vessels can be reduced through reliable and explicit incentives for license agreements, sufficient resources, and political support for community-based solutions. Stability in Somalia is increasing while pirate attacks have declined significantly from their peak in the mid-2000s. Today, international donors and aid agencies are investing in coastal communities and artisanal fishing businesses. To succeed, these investments must promote sustainability while stabilizing the economy and promoting food security. Short-term investments without long-term planning or may result in overfishing and declining profits, ultimately exacerbating local frustration at international actors. Finally, these investments will fail if the international community and Somali authorities fail to reign in foreign illegal fishing in Somali waters.

Author Contributions

SG and PR designed the research and created the fishery time line. SG conducted the catch reconstruction and sustainability analysis. PR conducted the analysis of AIS data. All authors contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the One Earth Future Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Parts of the research presented here are updated from and based on earlier work presented in the report Securing Somali Fisheries, cited here as Glaser et al. (2015). We are indebted to many Somalis who provided photographs, stories, and information about their lives as fishers, particularly Yusuf Abdilahi Gulled Ahmed and Jama Mohamud Ali. We are incredibly grateful for expert feedback from people who have lived and worked in Somalia and the region, including Julien Million, Andy Read, Marcel Kroese, Per Erik Bergh, Jorge Torrens, Kifle Hagos, and Stephen Akester. We wish to thank the team at Oceans Beyond Piracy, including Jon Huggins, Jerome Michelet, Jens Vestergaard Madsen, John Steed, Matthew Walje, Ben Lawellin, and Peter Kerins. We had significant assistance from Shuraako members Abdikarim Gole and Mahad Awale who spoke directly with Somali fishers. Dyhia Belhabib, Stephen Akester, Rashid Sumaila, Steve Trent, Dirk Zeller, Christopher Costello, and Daniel Ovando provided early technical review. At OEF, we thank Tim Schommer, Andrea Jovanovic, Jean-Pierre Larroque, and Laura Burroughs. exactEarth provided a significant amount of satellite Automatic Identification System data. Andy Hickman provided data, photographs, and interviews that were invaluable for validating our estimates of foreign fishing.

References

African Development Solutions (2015). Illegal Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing in the Territorial Waters of Somalia. Nairobi: African Development Solutions.

Google Scholar

Agnew, D. J., Pearce, J., Pramod, G., Peatman, T., Watson, R., Beddington, J. R., et al. (2009). Estimating the worldwide extent of illegal fishing. PLoS One 4:e4570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004570

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alverson, D. L., Freeberg, M. H., Pope, J. G., and Murawski, S. A. (1994). “A global assessment of fisheries bycatch and discards,” in Paper presented at the FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 339, (Rome: FAO).

Google Scholar

Anon (1976). Report on Cruise No. 5 of R/V “Dr. Fridtjof Nansen”. Indian Ocean Fishery and Development Programme - Pelagic Fish Assessment Survey North Arabian Sea. Bergen: Institute of Marine Research.

Google Scholar

Anon (2010a). Coastal Livelihoods in the Republic of Somalia. Agulhas and Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystems Project. Available at: http://www.asclme.org/reports2013/Coastal%20Livelihoods%20Assessments/48%20ASCLME%20CLA%20Somalia%20final%20draft%2022-11-2010.pdf

Google Scholar

Anon (2010b). Toxic waste behind Somali pirates. (8 May). Project Censored. Available at: http://www.projectcensored.org/3-toxic-waste-behind-somali-pirates/ (accessed December 1, 2014).

Google Scholar

Anon (2012). Summary Report FAO TCPF Fisheries Mission to Somaliland and Puntland (2505/R/01D).

Google Scholar

Anon (2013). Somalia: Puntland Seizes Five Illegal Fishing Boats, 78 Iranians Arrested. (April 24). All Africa/Garowe Online. Available at: http://www.somalilandlaw.com/somaliland_investment_guide.pdf (accessed November 15, 2014).

Google Scholar

Anon (2015a). Auditor-General Breaks Silence Over Illegal Fishing. (January 23). Somali Agenda. Available at: https://somaliagenda.com/auditor-general-breaks-silence-illegal-fishing/.

Google Scholar

Anon (2015b). Somalia: Fishermen protest against illegal fishing. Horseed Media.

Google Scholar

Anon (2015c). Somali’s Shabaab holds Iran Fishing Boat. (13 May). World Bulletin/News Desk. Available at: http://www.worldbulletin.net/todays-news/159123/somalias-shabaab-holds-iran-fishing-boat (accessed May 15, 2015).

Google Scholar

BBC (2014). Somaliland seizes Yemeni and Egyptian vessels. (December 17). London: BBC.

Google Scholar

BBC (2015). Somalia profile – Timeline. (May 5). London: BBC.

Google Scholar

Berbera Maritime and Fisheries Academy (2013). Business Plan. Berbera: Berbera Maritime and Fisheries Academy.

Google Scholar

Bihi, A. I. (1984). L’ Impact Potentiel des Activites Socio-Economiques sur l’ Environnement Marin et Côtier de la Réegion de l’ Afrique de l’ ’Est: Rapports Nationaux, in Mers Regionales. Programme des Nations Unies Pour l’Environment. Available at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/9701/Coastal_marine_environmental_problems_Somalia_rsrs084.pdf (accessed October 3, 2014).

Google Scholar

Bocha, G. (2012). Fishermen living in near destitution since October ban. (February 18). The Daily Nation. Available at: http://www.nation.co.ke/news/Kenyan-fishermen-living-in-near-destitution/-/1056/1330558/-/ft4ick/-/index.html (accessed September 30, 2014).

Google Scholar

Burale, D. M. (2005). FAO Post Tsunami Assessment Mission to Central and South Coast of Somalia (OSRO/SOM/505/CHA). Rome: FAO.

Google Scholar

Cashion, T., Glaser, S. M., Persson, L., Roberts, P. M., and Zeller, D. (2018). Fisheries in Somali waters: reconstruction of domestic and foreign catches for 1950 – 2015. Mar. Pol. 87, 275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.10.025

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chassot, E., Dewals, P., Floch, L., Lucas, V., Morales-Vargas, M., and Kaplan, D. (2010). Analysis of the Effects of Somali Piracy on the European Tuna Purse Seine Fisheries of the Indian Ocean. Report no (IOTC-2010-SC-09), Rome, FAO.

Google Scholar

Coastal Development Organization (2013). Illegal Fishing by Foreign Trawlers Looms Across Somalia. Somalia: Coastal Development Organization.

Google Scholar

Collie, J. S., Hall, S. J., Kaiser, M. J., and Poiner, I. T. (2000). A quantitative analysis of fishing impacts on shelf-sea benthos. J. Anim. Ecol. 69, 785–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00434.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Costello, C., Ovando, D., Hilborn, R., Gaines, S. D., Deschenes, O., and Lester, S. E. (2012). Status and solutions for the world’s unassessed fisheries. Science 338, 517–520. doi: 10.1126/science.1223389

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dayton, P. K., Thrush, S. F., Agardy, M. T., and Hofman, R. J. (1995). Environmental effects of marine fishing. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 5, 205–232. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3270050305

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dua, J. (2013). A sea of trade and a sea of fish: piracy and protection in the Western Indian Ocean. J. East. Afr. Stud. 7, 353–370. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2013.776280

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

EJF (2015). Oman Takes Decisive Port Measures to Block Suspect Fishing Vessels. (May 22). Undercurrent News. Available at: http://www.undercurrentnews.com/2015/05/22/ejf-oman-takes-decisive-port-measures-to-block-suspect-fishing-vessels/ (accessed May 26, 2015).

Google Scholar

Federal Republic of Somalia Ministry of Natural Resources (2014). A Review of the Somali Fisheries Law (Law No. 23 of November 30, 1985), in Accordance with Article 79, Paragraph (d) of the Federal Constitution of Somalia. Somalia: Federal Republic of Somalia Ministry of Natural Resources.

Google Scholar

Froese, R., and Pauly, D. (2014). FishBase. Available at: www.fishbase.org (accessed May 1, 2015).

Google Scholar

Fry, E. (2009). Fishing for Trouble. (March 29). Khlong Toei: Bangkok Post.

Google Scholar

GEBCO Compilation Group (2019). GEBCO 2019 Grid. doi: 10.5285/836f016a-33be-6ddc-e053-6c86abc0788e

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Glaser, S. M. (2015). Blockade of Yemeni ports has unintended consequences on food security, Somali fishing industry. (April 23) Blog. New Security Beat. Available at: https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2015/04/blockade-yemeni-ports-unintended-consequences-food-security-somali-fishing-industry/ (accessed April 1, 2018).

Google Scholar

Glaser, S. M., Roberts, P. M., Mazurek, R. H., Hurlburt, K. J., and Kane-Hartnett, L. (2015). Securing Somali Fisheries. Denver, CO: One Earth Future Foundation.

Google Scholar

Gomez, J. D., and Jiminez, J. R. V. (1994). Methods for the theoretical calculation of wing and door spread of bottom trawls. J. Northwest Atl. Fish. Sci. 16, 41–48. doi: 10.2960/j.v16.a4

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Government of Somaliland Ministry of Trade and Investment (2014). An Investment Guide to Somaliland Opportunities and Conditions 2013–2014. Available at: http://www.somalilandlaw.com/somaliland_investment_guide.pdf (accessed April 14, 2015).

Google Scholar

Haakonsen, J. M. (1983). “Somalia’s fisheries case study,” in Paper Presented at the Case Studies and Working Papers Presented at the Expert Consultation on Strategies for Fisheries Development, (Rome: FAO).

Google Scholar

Hansen, S. J. (2011). Debunking the piracy myth. How illegal fishing really interacts with piracy in East Africa. RUSI J. 156, 26–31. doi: 10.1080/03071847.2011.642682

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hendrix, C. S., and Brinkman, H.-J. (2013). Food insecurity and conflict dynamics: causal linkages and complex feedbacks. Stability 2:26. doi: 10.5334/sta.bm

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hiddink, J. A., Jennings, S., Sciberras, M., Szostek, C. L., Hughes, K. M., Ellis, N., et al. (2017). Global analysis of depletion and recovery of seabed biota after bottom trawling disturbance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 8301–8306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618858114

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC] (2008). Updated analysis of the SFA 2008 PS data: 2008 Effects of the Closed area in Somalia (IOTC-2008-SC-INF27). Available at: http://www.iotc.org/documents/updated-analysis-sfa-2008-ps-data-2008-effects-closed-area-somalia (accessed January 15, 2015).

Google Scholar

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC] (2010). Resolution 08/01. Mandatory Statistical Requirements for IOTC Members and Cooperating Non-Contracting Parties. Available at: http://www.iotc.org/cmm/resolution-1002-mandatory-statistical-requirements-iotc-members-and-cooperating-non-contracting (accessed January 15, 2015).

Google Scholar

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC] (2013). Examination of the Effects of Piracy on Fleet Operations and Subsequent Catch and Effort Trends (IOTC-2013-SC16-13[E]). Available at: http://www.iotc.org/documents/examination-effects-piracy-fleet-operations-and-subsequent-catch-and-effort-trends (accessed September 29, 2014).

Google Scholar

Indian Ocean Tuna commission [IOTC] (2014). Report of the 18th Session of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1–5 June 2014. (IOTC-2014-S18-R[E]). Available at: www.iotc.org/sites/default/files/documents/2014/06/IOTC-2014-S18-RE.pdf

Google Scholar

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission [IOTC] (2015). Report on presumed IUU Fishing Activities in the EEZ of Somalia (IOTC-2015-S19-Inf01). Available at: http://www.iotc.org/documents/report-presumed-iuu-fishing-activities-eez-somalia

Google Scholar

Kaiser, M. J., Clarke, K. R., Hinz, H., Austen, M. C. V., Somerfield, P. J., and Karakassis, I. (2006). Global analysis of response and recovery of benthic biota to fishing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 311, 1–14. doi: 10.3354/meps311001

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Katz, A. (2012). Fighting Piracy Goes Awry with Killings of Fishermen. (September 16) Bloomberg Business. Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-09-16/fighting-piracy-goes-awry-with-killings-of-fishermen (accessed November 15, 2014).

Google Scholar

Kulmiye, A. J. (2001). Militia Versus Trawlers: Who is the Villain? Kenya: The East African Magazine.

Google Scholar

Kulmiye, A. J. (2010). Assessment of the Status of the Artisanal Fisheries in Puntland Through Value Chain Analysis. Newyork, NY: UN Development Programme.

Google Scholar

Le Manach, F., Chavance, P., Cisneros-Montemayor, A., Lindop, A., Padilla, A., Schiller, L., et al. (2016). “Global catches of large pelagic fishes, with emphasis on the high seas,” in Global Atlas of Marine Fisheries: A Critical Appraisal of Catches and Ecosystem Impacts, eds D. Pauly, and D. Zeller, (Washington, DC: Island Press).

Google Scholar

Lehr, P., and Lehmann, H. (2007). “Somalia – pirates’ new paradise,” in Violence at Sea: Piracy in the Age of Global Terrorism, ed. P. Lehr, (New York, NY: Routledge), doi: 10.4324/9780203943489

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lovatelli, A. (1996). Artisanal Fisheries Final Report. European Commission Rehabilitation Programme for Somalia. Nairobi: EC Somalia Unit.

Google Scholar

MarineTraffic.com (2015). Greko 1. Available at: http://www.marinetraffic.com/ais/details/ships/shipid:905264/mmsi:-8615679/imo:8615679/vessel:GREKO_1 (accessed August 11, 2015)Google Scholar

McClanahan, T. R., Allison, E. H., and Cinner, J. E. (2015). Managing fisheries for human and food security. Fish Fish. 16, 78–103. doi: 10.1111/faf.12045

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Megalommatis, M. (2008). Somali Piracy – the Other Side. (December 8). Ocnus.net. Available at: http://www.ocnus.net/artman2/publish/Analyses_12/Somali_Piracy_-_The_Other_Side.shtml (accessed October 16, 2014).

Google Scholar

Mills, C. M., Townsend, S. E., Jennings, S., Eastwood, P. D., and Houghton, C. A. (2006). Estimating high resolution trawl fishing effort from satellite-based vessel monitoring system data. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 64, 248–255. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsl026

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Murphy, M. N. (2011). Somalia: the New Barbary? Piracy and Islam in the Horn of Africa. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Google Scholar

Musse, G. H., and Tako, M. H. (1999). Illegal Fishing and Dumping Hazardous Wastes Threaten the Development of Somali Fisheries and the Marine Environments,” in Tropical Aquaculture and Fisheries Conference 99, held on 7th–9th September 1999, Park Royal Hotel, Terengganu, Malaysia. Available at: http://www.geocities.ws/gabobe/illegalfishing.html (accessed October 16, 2014).

Google Scholar

Oceans Beyond Piracy (2014). The State of Maritime Piracy Report 2014. Denver, CO: One Earth Future Foundation.

Google Scholar

Oceans Beyond Piracy (2015). OBP Issue Paper: Will Illegal Fishing Ignite a Preventable Resurgence of Somali Piracy? Available at: http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/publications/obp-issue-paper-will-illegal-fishing-ignite-preventable-resurgence-somali-piracy (accessed March 21, 2015).

Google Scholar

Pauly, D., Belhabib, D., Blomeyer, R., Cheung, W. W. W. L., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Copeland, D., et al. (2014). China’s distant-water fisheries in the 21st century. Fish Fish. 15, 474–488. doi: 10.1111/faf.12032

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Persson, L., Lindop, A., Harper, S., Zylich, K., and Zeller, D. (2015). “Failed state: reconstruction of domestic fisheries catches in Somalia 1950–2010,” in Fisheries catch reconstruc- tions in the Western Indian Ocean, 1950–2010, eds F. Le Manach, and D. Pauly, (Vancouver: University of British Columbia).

Google Scholar

Pilskaln, C. H., Churchill, J. H., and Mayer, L. M. (1998). Resuspension of sediment by bottom trawling in the gulf of maine and potential geochemical consequences. Conserv. Biol. 12, 1223–1229. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.0120061223.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pitcher, T. J., Watson, R., Forrest, R., Valtysson, H. P., and Guénette, S. (2002). Estimating illegal and unreported catches from marine ecosystems: a basis for change. Fish Fish. 3, 317–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2979.2002.00093.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Puntland State of Somalia Office of Coast Guard Forces (2006). Letter to the Supreme Court of Royal Thai Government, subject: Release of Somali Nationals Detained in Thailand. (March 3). Available at: http://www.somalitalk.com/2006/thailand/letter2.pdf (accessed December 1, 2014).

Google Scholar

Schbley, G., and Rosenau, W. (2013). Piracy, Illegal Fishing, and Maritime Insecurity in Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania. Arlington, VA: CAN.

Google Scholar

Shifco (1998). Final Mission Report, Somalia. (November 18). Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/inspections/vi/reports/somalia/vi_rep_soma_1522-1998_en.pdf (accessed 15 October, 2014)Google Scholar

Somali Democratic Republic Ministry of Fisheries, and Marine Transport [MFMT] (1988). Yearly Fisheries and Marine Transport Report 1987/1988. Mogadishu: MFMT.

Google Scholar

Somali Democratic Republic Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources [MFMR] (1985). Guidelines for Fisheries Joint Venture with Foreign Partners. Mogadishu, Somalia. Available at: http://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/som2144.pdf (accessed September 30, 2014).

Google Scholar

Stop Illegal Fishing (2016). FISH-i Africa: Issues, Investigations, and Impacts. Gaborone: Stop Illegal Fishing.

Google Scholar

Stop Illegal Fishing (2017). A ghost Vessel in Somali Waters: Greko 1. (March 13). Available at: http://www.iuuwatch.eu/2017/03/ghost-vessel-somali-waters-greko-1/ (accessed March 15, 2017).

Google Scholar

Stop Illegal Fishing (2018). 22 Thai crewmembers await repatriation from Thai-owned ‘Somali Seven’ fishing vessels. (February 20). Available at: https://stopillegalfishing.com/news-articles/22-thai-crewmembers-await-repatriation-thai-owned-somali-seven-fishing-vessels/ (accessed March 1, 2018).

Google Scholar

Stromme, T. (1984). Cruise report R/V Dr. Fridtjof Nansen: second fisheries resource survey north-east coast of Somalia 24–30 August 1984. Reports on Surveys with the R/V Dr Fridtjof Nansen. Bergen: Norway: Institute of Marine Research.

Google Scholar

Sumaila, U. R., and Bawumia, M. (2014). Fisheries, ecosystem justice and piracy: a case study of Somalia. Fish. Res. 157, 154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2014.04.009

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

United Nations Security Council (2013). Report on Somalia of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea (S/2013/413). (July 12). Available at: http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2013_413.pdf (accessed September 30, 2014).

Google Scholar

Van Zalinge, N. P. (1988). Summary of Fisheries and Resources Information for Somalia. Report Commission for the FAO. Rome: FAO.

Google Scholar

Waldo, M. A. (2009). The Two Piracies: Why the World Ignores the Other? (January 8). WardheerNews.com. Available at: https://issuu.com/abelgalois/docs/somalias_twin_sea_piracies (accessed September 29, 2014).

Google Scholar

Waugh, S. M., Filippi, D. P., Blyth, R., and Filippi, P. F. (2011). Assessment of Bycatch in Gillnet Fisheries. Report to the Convention of Migratory Species. Available at: http://www.cms.int/en/document/assessment-bycatch-gill-net-fisheries (accessed May 13, 2015).

Google Scholar

Weldemichael, A. T. (2012). Maritime corporate terrorism and its consequences in the western Indian Ocean: illegal fishing, waste dumping and piracy in twenty-first-century Somalia. J. Indian Ocean Reg. 8, 110–126. doi: 10.1080/19480881.2012.730747

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yassin, M. (1981). Somalia: Somali Fisheries Development and Management. Available at: https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_projects/9019s7088 (accessed March 26, 2015).

Google Scholar

Zeller, D., Booth, S., Davis, G., and Pauly, D. (2007). Re-estimation of small-scale fishery catches for U.S. flag-associated island areas in the western Pacific: the last 50 years. Fish. Bull. 105, 266–277.

Google Scholar

Keywords: IUU fishing, Somalia, fisheries conflict, distant water fishing nations, sustainability, fisheries governance, trawling, foreign fishing

Citation: Glaser SM, Roberts PM and Hurlburt KJ (2019) Foreign Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing in Somali Waters Perpetuates Conflict. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:704. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00704

Received: 01 May 2018; Accepted: 01 November 2019;

Published: 06 December 2019.

Edited by:Philippe Le Billon, The University of British Columbia, Canada

Reviewed by:Reg Alan Watson, University of Tasmania, Australia

Anja Shortland, King’s College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2019 Glaser, Roberts and Hurlburt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah M. Glaser, sglaser@oneearthfuture.org

View full image

View full image View full image

View full image