For decades, Somalia has faced recurring famines and food crises resulting from droughts, poor government policies, or inaction amid civil war. Could the country’s fisheries become a beacon of hope for food security and poverty alleviation, despite piracy and poaching revealed by a recent reassessment of fish catches?

WRITTEN BY LO PERSSON & IDA KARLSSON

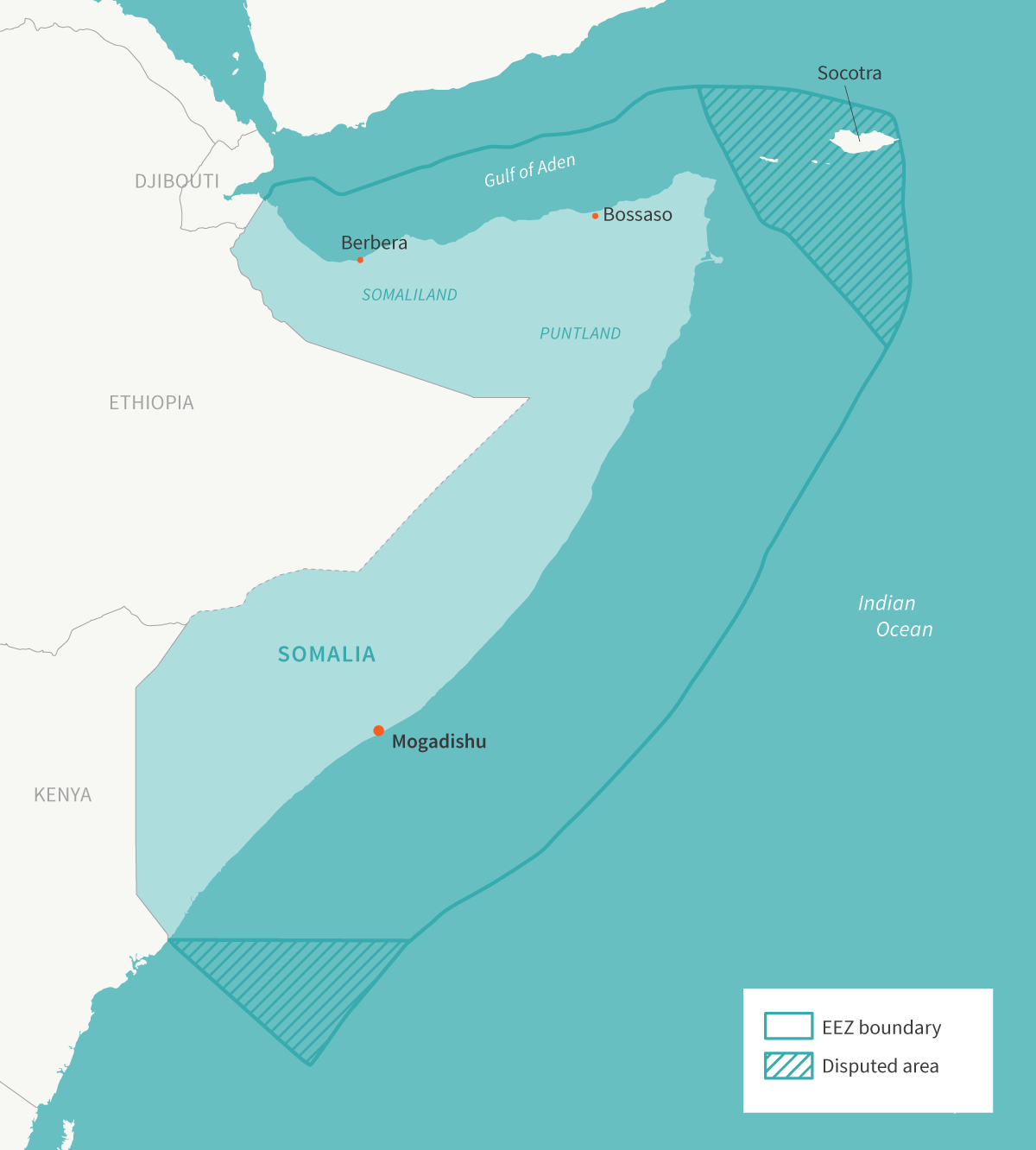

The waters surrounding Somalia – the tip of the Horn of Africa – are rich with fish. Tuna occasionally throng here, among other fish that fetch high market prices. With its long coastlines on the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden, the country has great potential to generate income from fishing. That makes it of interest to investors and international donor groups looking to help the people who live in poverty here – through fisheries.

In a land where people were predominantly nomads, fishing is a relatively new way to earn a living. Small-scale fishers face many challenges here, ranging from lack of fishing traditions to potential overfishing and competition from illegal foreign fishing, all against the backdrop of historic and ongoing conflict, as well as periodic drought that leads to national food crises.

A major concern for a sustainable development of fishing has also been the lack of reliable fishery statistics. A reconstruction of the catches made in Somali waters highlights how foreign fleets of fishing vessels poach fish and profits, preventing the full potential of the fishing sector to generate livelihoods, income, and revenue for individual fishers and the state.1

These findings could be used when setting up sustainable fishing quotas to steer away from overfishing. But widespread poverty, a lack of institutions to enforce and maintain such quotas, and security issues remain stumbling blocks. These many challenges require a broad approach when looking for solutions that consider both social and ecological factors on many different scales, from the local to the global.

A fishing boat leaves Berbera Harbor, in the Gulf of Aden along the north coastline of Somalia. Copyright Jean-Pierre Larroque, One Earth Future Foundation.

Spotlight on fishing

After severe droughts in the 1970s, the socialist regime in Somalia, led by President Mohamed Siad Barre, relocated nomadic people into fishing cooperatives. The move was intended to increase the importance of the fishing sector in an effort to reduce nomadic people’s vulnerability to droughts.

The Soviet Union supported the fishing cooperatives and donated fishing gear and motorised fishing boats. But obstacles dashed high hopes for the fishing sector: a lack of fishing traditions, limited knowledge of how to repair boats and fishing gear, a shortage of spare parts, and the absence of storage facilities. The civil war and the collapse of the government in 1991 made spare parts for motorboats even less accessible. It also exacerbated the lack of reliable fishery statistics for the region, as a functioning government remained a dream.

Even so, over the past two decades, fishing started to grow along the coast of Somalia. The nascent fishing sector now employs over 70,000 people in a country of more than 11 million, and is thought to contribute US$135 million per year to the economy, or around 1-2% of Somali GDP.

Somali fishers still struggle. “Our challenge is that we are relying on fishing equipment that was used 100 years ago,” says Jama Ahmed Mohamed, owner of the Alla Aamin Fishing Company in Berbera, Somaliland. “But the biggest challenge is foreign ships that come to our sea illegally at night,” he said in an interview with One Earth Future, a non-profit foundation that assisted in reconstructing Somalia’s missing catches.

Jama Ahmed Mohamed holds a skipjack tuna at Alla Aamin Fishing Company in Berbera. Copyright Jean-Pierre Larroque, One Earth Future Foundation.

Foreign vessels’ theft

Data on what is being caught by whom in Somali waters have been scarce. Since the collapse of the government in 1991, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has not been able to update the fisheries catch statistics for the country, and the data from before the civil war are incomplete, with no distinction between industrial fleet catches from those of small-scale fishers.

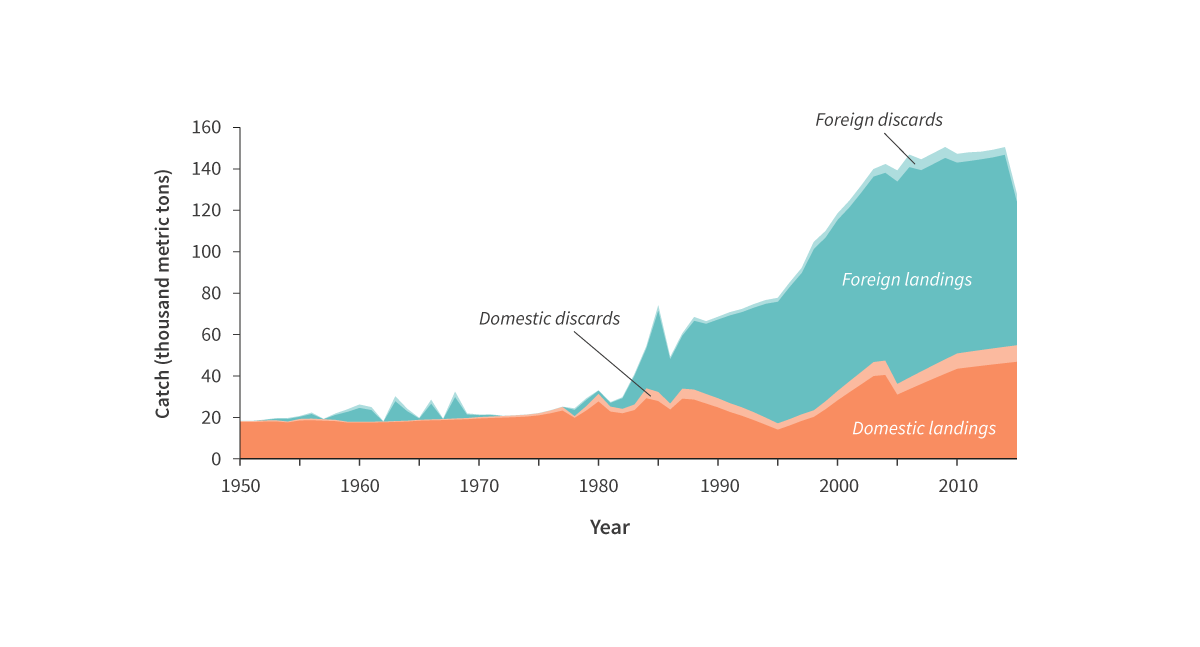

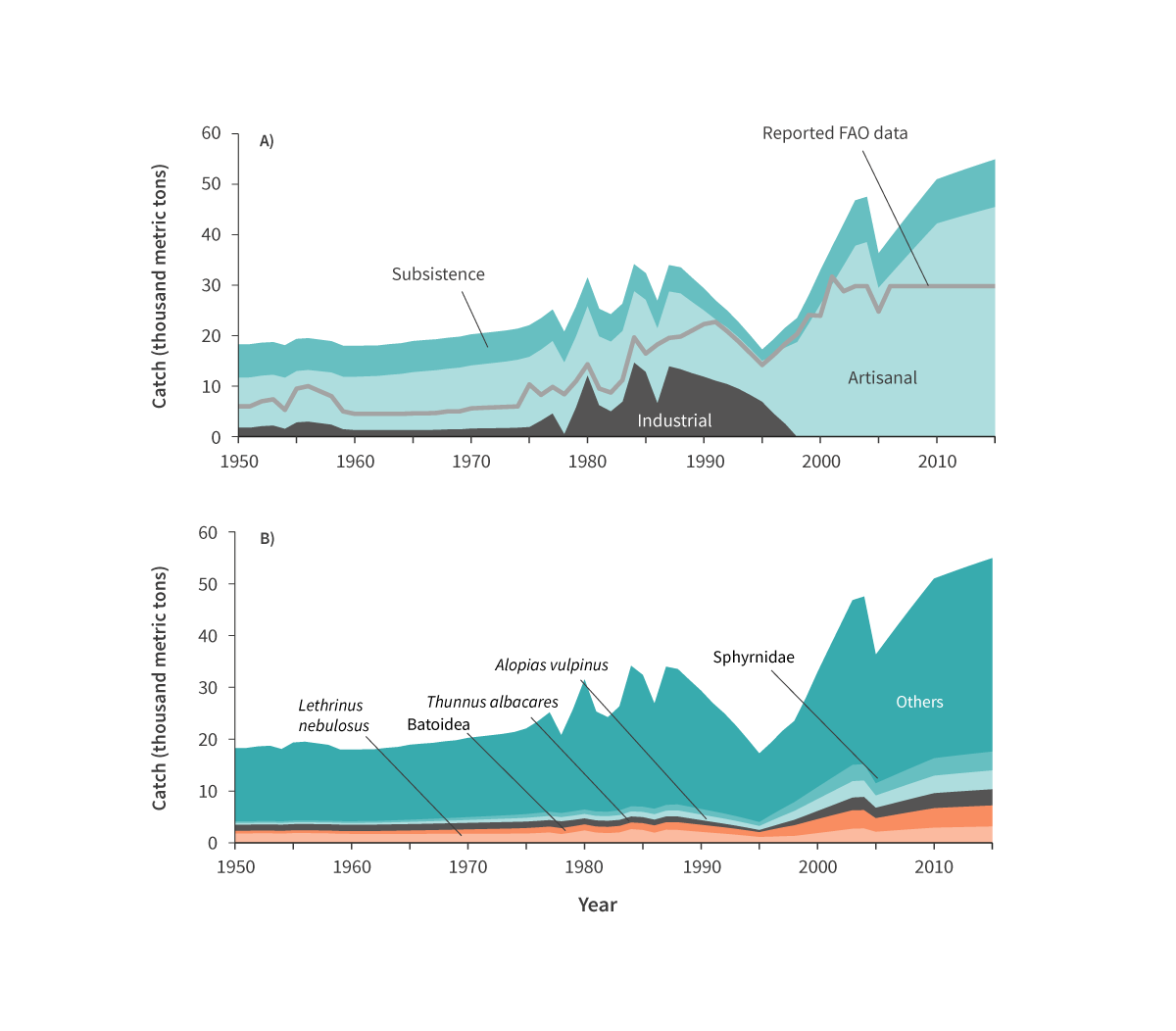

But recent detective work by researchers from around the world, including Lo Persson, lead author of this piece, has revealed a fuller picture. Extensive foreign fishing in Somali waters has extracted about two-thirds of the total reconstructed catch since the 1990s. And the domestic catch has been about 80% higher over the last six decades than what has been reported in official FAO statistics.2

The team, as part of the Sea Around Us project at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver in collaboration with One Earth Future, based in Colorado, built this catch reconstruction from 1950 to 2015 for the 200-km offshore economic zone over which Somalia should have sovereign control. They unearthed all the records they could find, from academic literature, industrial fishing statistics, local fishing experts, and newspaper articles. The few existing documents about Somali fishing and catches, of which only two were official documents with catch statistics from the Somali government, were in different libraries scattered across the world.

Map: E. Wikander/Azote.

Among the more important resources the team used was a report written by Jan M Haakonsen, a Norwegian researcher who visited newly formed fishing cooperatives in 1978 to see how pastoralist nomads were adapting to their new lives as fishers.3 Haakonsen’s report for the FAO showed how the cooperatives were functioning, including the number of boats that helped the team to create a catch estimate for 1978, for example.

Other publications such as the 2001 Ocean Yearbook fleshed out the legal problems of controlling access to Somali marine areas in the absence of a functioning government, as well as insights into foreign fishing and the close link to piracy. That connection had already been made in the late 1990s, but an increase was soon to come.4

Using these and other documents, the team made a host of assumptions, including the number of boats present, fish discarded by industrial trawlers, catches by subsistence fishers, and more. Taken together, they developed a more accurate picture of the catches from Somali fisheries. To estimate the extent of foreign fishing in Somali waters, they also used information on old and new partnerships, such as an official Somalia-Iraq fishing company, agreements with Chinese and Korean fishing fleets, and even unofficial fishing licences granted by warlords to international corporations.

Current fishing efforts offshore of Somalia – both domestic and international – amount to over 125,000 tonnes of fish and shellfish a year, according to the reconstruction, an increase from about 16,500 tonnes a year in 1950. Foreign fishing far outweighed domestic fishing, contributing about two-thirds of the reconstructed catch since the beginning of the 1990s. That means that ships under foreign flags may be contributing to a possible decline in fish stocks in the region.

Total reconstructed domestic and foreign landings and discards from Somali waters, as reconstructed by the author and colleagues. See footnote 2. Modified by E. Wikander/Azote.

Developing countries typically have limited resources for surveillance of their marine territories. Researchers have estimated that the total illegal and unreported catches around the world amount to between 11 and 26 million tonnes, at a value of US$10 billion to more than $23 billion.5 Somalia loses hundreds of millions of dollars every year due to unregulated foreign fishing: in 2005 alone, the value of illegal catches was estimated to be about US$300 million.6

“The small-scale fishing sector in Somalia has not reached its full potential, and foreign donor agencies see the fishing sector as a good investment,” says Sarah Glaser, associate director of the Secure Fisheries programme at One Earth Future and a co-author of the catch reconstruction. However, the illegal foreign fishing in Somali waters continues, and foreign boats have been accused of attacking Somali fishers.

Some researchers and journalists have suggested that the illegal foreign fishing in Somali waters led to the rise of piracy in the region, as local fishers retaliated against foreign fleets. However, piracy soon turned into big business for warlords and criminals. In 2008, attacks increased by 200%, as Somali pirates attacked 111 ships in the region, and Somali waters soon became the most heavily pirated in the world.7 Piracy led tuna fishing boats to shift their efforts away from Somalia, and fishing companies defined a large exclusion zone off the Somali coast in 2008 that represented more than 25% of the total catch from the previous decade.8

The research team reconstructed the domestic catches in Somali waters from 1950–2015 by fisheries sector with reported catches overlaid as a line (A) and by species or major taxa (B). “Others” includes 38 additional taxonomic categories (see www.seaaroundus.org). See footnote 2. Modified by E. Wikander/Azote.

The protracted civil war and the collapse of the government in 1991 left Somali fisheries uncontrolled and the waters unguarded. The catch reconstruction shows that the Somali small-scale fishing sector grew in the late 1990s, taking advantage of the lack of governmental control that was thought to hinder development during the Siad Barre era. Several foreign fleets – from Asian countries and from the EU but flying flags from countries outside the EU to avoid regulations – took advantage of the unguarded waters, catching lobster and large pelagic fish like tuna and billfish.1

“The occurrence of extensive illegal foreign fishing in the waters of a sovereign state shows an astounding lack of control by the flag state,” or the state where the fishing vessel is registered, according to Dirk Zeller, a professor at the University of Western Australia and a co-author of the catch reconstruction. It also “illustrates the international trans-boundary criminal activity of illegal fishing. The international community bears a responsibility to help support sustainable and ethical fishing through investment, regulation, and control of its vessels, and respect for international law.”

International community responsibility

Putting an end to illegal fishing could prove to be an important step in supporting Somalia on its path to building stability. A fragile democracy has emerged, with the establishment of a parliament in 2012 and the election of a new president.

But the government still needs help to face the many other ongoing problems in Somalia, in addition to ongoing food crises and drought. Humanitarian response agencies such as the Red Cross, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and UN Development Programme (UNDP) remain active in the country and also hope to improve access to maternal and child healthcare, strengthen the respect for human rights, and increase job opportunities in the country.

After the 1991 collapse of the government, the struggle for power among different clans, warlords, and rebel groups left civilians in dire straits, which were periodically compounded by droughts. The international community attempted to establish transitional governments but met resistance, mainly from Islamist groups and especially from al-Shabaab, the Islamist militant group formed in 2006. The latest severe drought in 2017 led to large-scale food insecurity that affected more than 6 million people in the country. Today, there are over 870,000 Somalis registered as refugees in the Horn of Africa and Yemen, and around 2.1 million are displaced within Somalia, according to the UNHCR. An estimated 5.4 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance and, while malnutrition has decreased, it remains a serious concern.

The FAO is attempting to bolster fishing in Somalia as a solution to many of these issues and more: improving livelihoods, establishing peace and security, and addressing gender issues, among others. One FAO programme, Coastal Communities Against Piracy, is supported in a partnership with the European Union and seeks to build strong coastal communities through fishing that enhances food security and contributes to people’s incomes. As part of another FAO programme, local youth have been trained in new fishing techniques on the outskirts of the port city of Bosaso.

These young fishers are encouraged to avoid fishing grounds that are vulnerable to overfishing, such as coral reefs. They have also been given larger and better-equipped boats that can reach waters with more profitable species, such as tuna. While the threats to some tuna species and other fish in the Indian Ocean remain high, the hope is that education will help make the fishery more sustainable.

Other FAO programmes have trained local women to process fresh-caught fish for sale, drying it in the sun to prevent it from spoiling; in addition to their salary, they get fresh fish to take home to feed their families. And men and women have learned boat-building techniques, to produce safer fishing vessels locally. Meanwhile, the FAO hopes its fishing “coaches” will pass on best practices and local knowledge.

Yet according to the FAO, fishing remains less than 1% of GDP in a country with one of the longest coastlines in Africa. Nomadic and agricultural lifestyles remain the most important for many Somalis, and unpredictable rainfall and droughts have hit the population hard. The lack of functioning government and other institutions worsened the consequences of the droughts.

Today, as the FAO and other organisations are trying again to make fisheries important, the local demand for fish is growing. They hope that the continued development of the Somali fishing sector could contribute to long-term food and economic security and help build resilience to conflict and disaster.6

Fishers in the Gulf of Aden returning home with their catch. Copyright Jean-Pierre Larroque, One Earth Future Foundation.

The recently reconstructed estimates of actual fish catches in Somali waters since 1950 could aid the creation of sustainable management plans and help to put a fair price tag on foreign fishing licensing agreements. But the nascent government, together with local institutions and actors, needs to make the plans, set up and administrate licensing agreements, and be able to enforce them. Support at an international level will also be needed to curb fishing by foreign vessels in Somali waters.

The new picture painted with the data reveals the importance of the small-scale fishing sector to Somalia and how much is lost every year to foreign and illegal fishing. To ensure that the country benefits from its marine resources and to remove the social justification for piracy, illegal fishing needs to be combatted and sustainable management plans put into place. Within this context, strengthening Somali fisheries will require broad approaches to solutions that account for political, social, and environmental aspects.

No comments:

Post a Comment